Bollen says in newly public EB-5 deposition that Janklow wanted him in Pierre

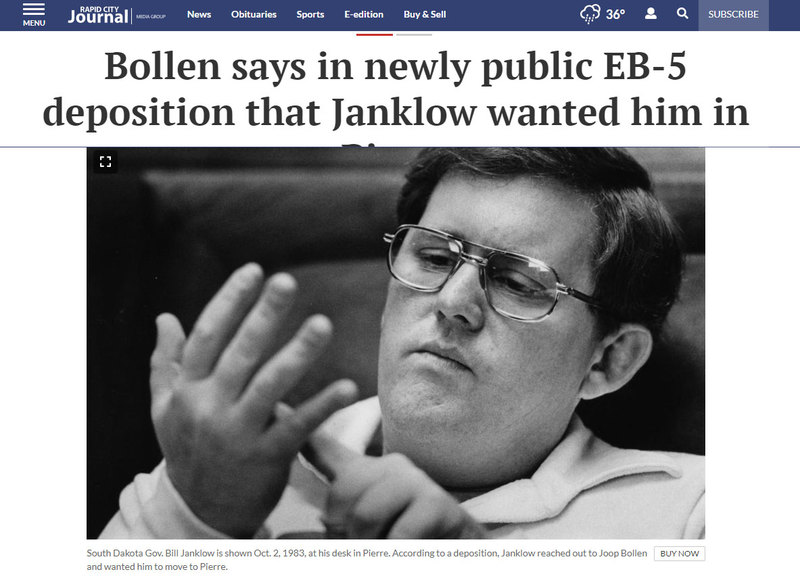

South Dakota Gov. Bill Janklow is shown Oct. 2, 1983, at his desk in Pierre. According to a deposition, Janklow reached out to Joop Bollen and wanted him to move to Pierre.

A new public document in a lawsuit indicates that the relationship between state government and Joop Bollen — the central figure in South Dakota’s fatal and convoluted EB-5 scandal — began to develop and strengthen earlier than previously reported and was cemented during the administration of the late former governor Bill Janklow.

That’s one of numerous revelations in the transcript of a four-hour deposition of Bollen that includes previously unknown details about his life, his early involvement with state government, and his role in converting a relatively small, international dairy-recruitment project into a lucrative investment-for-visa processing center. Another revelation was the extent to which Bollen insisted that high-ranking officials in the administration of former Gov. Mike Rounds, and officials at Northern State University and with the state Board of Regents, knew and approved of even the most controversial of his EB-5 activities.

The deposition was taken March 20 in Aberdeen, and the transcript became part of a public court file Wednesday when it was attached to another document as an exhibit.

Bollen said in the deposition that he began running a corporation in the 1990s that was housed at Northern State University in Aberdeen. He said the corporation was intended to help boost exports from South Dakota and was the precursor to what eventually became South Dakota’s EB-5 regional center. The early work was partially sponsored by state government, Bollen said, and it caught Janklow’s eye.

Sometime during the 1990s, according to Bollen, he went to the state capital city of Pierre with John Hutchinson, who was NSU’s president from 1993 to 1997, and Clyde Arnold, who was the dean of NSU’s business school, where they met with then-Gov. Janklow at his request and discussed Bollen’s ideas to boost manufacturing exports.

Joop Bollen

During deposition questioning by attorney Kasey Olivier, of Heidepriem, Purtell, Siegel & Olivier in Sioux Falls, Bollen described Janklow’s reaction.

Bollen: “He liked it. He liked my plans, I think. So he sent me an email if I had an interest to come to Pierre. But I told him, no, I didn’t want to go to Pierre.”

Olivier: “To go live in Pierre?”

Bollen: “To work. Yeah.”

The deposition was taken for a lawsuit in federal court known as SDIF Limited Partnership 2 v. Tentexkota LLC, et al.

Bollen manages SDIF Limited Partnership 2, which in 2009 pooled $32.5 million invested by 65 foreigners through the federal government’s EB-5 program and loaned it to Tentexkota. In exchange, the foreigners were given visas and then green cards granting them permanent residency in the United States.

Tentexkota — comprised of partners including W. Kenneth "Big Kenny" Alphin, of the country music duo Big & Rich — used the money to help convert Deadwood’s historic Homestake slime plant into the Deadwood Mountain Grand hotel-and-gaming resort, which opened in 2011.

Bollen is now seeking repayment of the loan, which is in default, but the Tentexkota partners want their personal loan guarantees voided. They claim Bollen duped them into signing the guarantees by falsely claiming they were a requirement of the EB-5 program.

The federal program at the heart of the lawsuit, EB-5, is named for the employment-based, fifth-preference visa. The program allows foreigners to obtain an EB-5 visa, and then permanent U.S. residency in the form of green cards, in exchange for investments of at least $500,000 in U.S. business projects that generate at least 10 jobs.

EB-5 investments are made with the assistance of regional centers, and Bollen ran a regional center on behalf of South Dakota as a state employee from 2004 to 2009, and then as a private contractor with the state from 2009 to 2013.

South Dakotans knew little about the state’s participation in the EB-5 program until 2013, when Richard Benda, a former state employee who worked closely with Bollen, was found dead of what was officially ruled a suicide by shotgun. It was later revealed that Benda had been facing potential prosecution for his alleged theft of $550,000 in state grant money that was intended for an EB-5-funded meatpacking plant in Aberdeen. At the time, Benda was leaving state government and going to work for Bollen.

Revelations about the details of EB-5 in South Dakota poured forth for several years in the courts and the media. After the scandal broke in 2013, it dogged the ultimately victorious 2014 U.S. Senate candidacy of Rounds, who succeeded Janklow as governor in 2003.

Mike Rounds

In February 2017, Bollen pleaded guilty to the little-known crime of “unauthorized disposal of personal property subject to a security interest” and was sentenced to a $2,000 fine and two years of probation. The charge arose from his diversion of $1.2 million from an account that was created to protect the state against EB-5 costs and liability. He eventually put most of the money back into the account — all but $167,000 was accounted for — but not before he had used some of the money to buy Egyptian artifacts.

In the newly revealed deposition taken for the Tentexkota litigation, Bollen, a 55-year-old Dutch immigrant who lives in Aberdeen, revealed details of his life, the beginnings of his involvement with state government, and the growth of the EB-5 program before it ended in scandal.

Netherlands to Aberdeen

Bollen said he was born in the Netherlands, in the town of Eindhoven, where he decided at the age of 17 that he wanted to emigrate to the United States.

He went to El Camino Real, Calif., as an exchange student; received a high school diploma from Calabasas High School; graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1986; earned a master’s in business administration in Arizona in 1987; and got a job with Continental Grain in Chicago, he said.

While traveling for Continental Grain, Bollen met his first wife, who was from Aberdeen. He said they married in 1990. That same year, Bollen said, he trained to work in financial securities for J.P. Morgan but opted instead for a business partnership with a man named Pyush Patel in Atlanta, where the two bought a liquor store.

The Patel partnership lasted only three to six months, Bollen said, before the two had a falling out, the details of which Bollen said he could not remember. (Nevertheless, Patel and Bollen later paired up again, and Bollen said during the deposition that he and Patel now jointly own a variety of apartment rentals and gas-convenience stores in Atlanta, plus some title-loan businesses and commercial rental properties.)

Of his move to Aberdeen in 1990, Bollen said, “ … my ex-wife was from here so that’s how I ended up coming back here.”

Bollen said his involvement with state government began during the early 1990s after he bought some real estate from the then-mayor of Aberdeen. Bollen did not say the name of the mayor in the deposition, but 1990 falls within the tenure of Tim Rich.

Bollen said he was encouraged by the mayor to talk with officials at Northern State University who wanted to set up an international outreach program, in part to increase exports from South Dakota.

Bollen said he was hired to run a corporation housed at NSU, and he began conducting workshops for South Dakota businesspeople who were interested in exporting. The workshops generated money for NSU, Bollen said, and the Janklow administration also funded some of the work through the Governor’s Office of Economic Development (GOED).

"Under the Janklow administration it was very clear that they wanted export promotion first,” Bollen said. “It eventually — the effect was that Janklow transferred the international department to Northern for export promotion.”

Bollen said that John Hilpert, who was president of NSU from 1997 to 2003, liked the partnership with the state because of the revenue it was bringing to the university and wanted a closer relationship.

“And because Hilpert wanted to anchor the relationship even wider with GOED, they asked me what can I do?” Bollen said. “And I said, ‘Well, I know that the state has been trying to attract foreign investment, but they never had any success. So that is something that I think I could contribute.’”

Dutch dairies to Korean investors

Bollen said that between 2000 and 2003 — which would have included the end of the Janklow administration and the start of the Rounds administration — he began shifting his focus from export promotion to the attraction of foreign investment in South Dakota, with encouragement from then-NSU President Hilpert.

Initially, Bollen recruited dairy farmers from his native country to establish dairies in South Dakota.

“I knew that the Netherlands, the government was pretty much telling these dairies, look, we don’t want you here,” Bollen said. “I knew the milk quota system was tough, and these Dutch dairy farmers were looking all over the world for alternatives.”

Bollen successfully recruited some dairy farmers who came to the United States on E-2 visas, but there was a problem. He said if the farmers ever quit their dairy business, E-2 visa requirements would’ve forced them to return to the Netherlands.

“And that is why I started searching for something that would give South Dakota comparative advantage over other states, such as Michigan, Ohio, that also were trying to recruit these Dutch dairy farmers,” Bollen said.

His search caused him to study different kinds of visas.

“And that is how I — you know, you had EB-1, EB-2, EB-3, EB-4, EB-5. You just kind of go through the employment base visas,” Bollen said.

Bollen discovered that he liked the EB-5 program, he said, because it allowed not only foreign investors but also their families to enter the United States and obtain permanent residency. Additionally, the program’s requirement that projects create at least 10 jobs could be calculated indirectly — in other words, a dairy that had only four employees could use a multiplier and claim it created additional jobs outside of its own business, such as a milk-truck driver and secretary for the trucking company.

So, Bollen said, in 2002 or 2003, he flew to Washington, D.C., and met with the head of the federal EB-5 program, housed within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Up to that point, he said, regional centers that were set up to receive EB-5 investments had been private entities. On behalf of South Dakota, Bollen said, he established the first state-run EB-5 regional center in 2004.

Then, he flew to Europe to recruit more dairy farmers.

“And tell them here, look, you can go to Michigan, you can go to Ohio, but you have an E-2 visa,” Bollen said. “If you come to South Dakota, you get a green card. So pretty much checkmate the other states.”

Bollen said the program ultimately financed $90 million worth of dairy farms along the Interstate 29 corridor.

The program eventually morphed into something more than a dairy-recruitment project. Bollen said that when the U.S. Department of Commerce published a new list of EB-5 regional centers, he was immediately inundated with calls from abroad, mostly from South Korea.

“People who wanted to come to the United States and wanted to find a way in,” Bollen said.

'I needed bigger projects'

Before long, Bollen said, regional centers popped up in more states, and South Dakota lost its competitive advantage in foreign dairy recruitment.

“I needed bigger projects,” he said. “And dairy farms were no longer cutting it. I knew Mike Rounds was very interested in the certified beef program.”

That’s how Bollen became involved in attracting EB-5 investments for a proposed meatpacking plant in Aberdeen called Northern Beef Packers, which was intended to process cattle that were certified as bred, born and raised in South Dakota. The project ultimately went through bankruptcy, leaving $80 million in unpaid debts, before it was reborn recently under new ownership as DemKota Ranch Beef.

When Bollen got involved with the Northern Beef Packers project, he met Richard Benda, who was Rounds' secretary of tourism and state development. Benda's job included oversight of the GOED. Bollen said it was clear that Benda and the state “wanted this beef project.”

Richard Benda

Richard Benda was ruled to have committed suicide while he was about to face criminal charges in a state immigration program scandal.

Journal file

“So I saw an opportunity from, hey, this is a chance for us to become competitive again,” Bollen said.

Bollen said investment in the beef plant came from Korea and China, in two rounds that each yielded about $35 million. More projects followed, and South Dakota’s EB-5 regional center took off.

Bollen said the original EB-5 model involved equity investments, in which banks vetted and financed projects to which foreigners contributed investments. But Bollen said South Dakota’s EB-5 center evolved around 2008 or 2009 to a model in which foreign investments were pooled and loaned to projects without the involvement of a bank.

“And the reasons for the loan model were pretty persuasive,” Bollen said, “and it had to do with exit strategy. If you’re an equity investor and after five years having a permanent green card, it’s a little harder to get out of a business than it would be with a loan that is coming due.”

SDRC Inc. is born

It was for similar reasons that Bollen said he created a private company called SDRC Inc. in early 2008 and assigned it some responsibility to help manage South Dakota’s EB-5 regional center. That move, when it was later revealed publicly, became a focal point of the EB-5 scandal among critics who described it as self-dealing — Bollen had still been a state employee under the supervision of NSU when he made the deal with his own company.

Bollen said in the deposition that one reason he created SDRC Inc. was to hire people to do the project vetting that was formerly done by banks. He said the intent was for NSU to eventually own SDRC Inc. That plan exploded in mid-2008, Bollen said, when a California company called Darley International, which had been helping to recruit EB-5 investors in China, claimed that Bollen and another investment recruiter had breached several aspects of their collective contract.

“And when Darley started that lawsuit all the bureaucrats just came to a shrieking halt and became scared,” Bollen said.

Bollen said he was eventually directed to completely turn over management of South Dakota’s EB-5 regional center from NSU to his private firm, SDRC Inc.

“So it was a meeting between the president of Northern and Richard Benda,” said Bollen, who did not provide a date for the meeting or say who was the president of NSU at the time (from 2008 to 2009, the university transitioned through three presidents). “They decided that I should go private and do it under contract with the governor’s office.”

An agreement to that effect between the Governor’s Office of Economic Development and Bollen’s SDRC Inc. was signed in late 2009. Bollen also left state employment at that time to run SDRC Inc.

“GOED knew what was happening. Northern knew what was happening. Board of Regents knew what was happening,” Bollen said. “That was their decision.”

To that point, fees collected as part of the EB-5 program had benefited NSU, Bollen said. Those fees then flowed to SDRC Inc. in amounts not fully disclosed in the deposition. Bollen said he and business partner Payush Patel took distributions from SDRC Inc. as stockholders in the company.

Deadwood Mountain Grand

Bollen said he became involved in the Deadwood Mountain Grand Project at the behest of one of the project partners, Ron Wheeler, whose long history of involvement with state government includes past service as the secretary of transportation and commissioner of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development.

“Ron Wheeler indicates that they’re looking for funding for a project,” Bollen said. “I like what I hear. I like Ron Wheeler’s past connection with Pierre. He is a man with a solid reputation. He advised that he has a group of investors that are very strong business people.”

Bollen said he sought personal loan guarantees because the project appeared too risky to sell to foreign investors without the guarantees.

Olivier, the attorney handling the deposition, drew an admission from Bollen that it was the first time he had obtained personal guarantees for an EB-5 project.

Bollen said the Tentexkota partners defaulted on their $32.5 million loan in 2016, which prompted the lawsuit for which the deposition was taken. Bollen said the investors in the SDIF Limited Partnership 2 decided to sue Tentexkota against his advice, which was to work out a settlement rather than engage in what to this point has been a two-year legal fight.

Mentions

- South Dakota Regional Center Inc.

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- Joop Bollen

- Deadwood Mountain Grand Hotel, Casino & Event Center

- Northern Beef Packers III

Litigation Cases

States

- South Dakota

Securities Disclaimer

This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to sell shares or securities. Any such offer or solicitation will be made only by means of an investment's confidential Offering Memorandum and in accordance with the terms of all applicable securities and other laws. This website does not constitute or form part of, and should not be construed as, any offer for sale or subscription of, or any invitation to offer to buy or subscribe for, any securities, nor should it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied on in any connection with, any contract or commitment whatsoever. EB5Projects.com LLC and its affiliates expressly disclaim any and all responsibility for any direct or consequential loss or damage of any kind whatsoever arising directly or indirectly from: (i) reliance on any information contained in the website, (ii) any error, omission or inaccuracy in any such information or (iii) any action resulting therefrom.