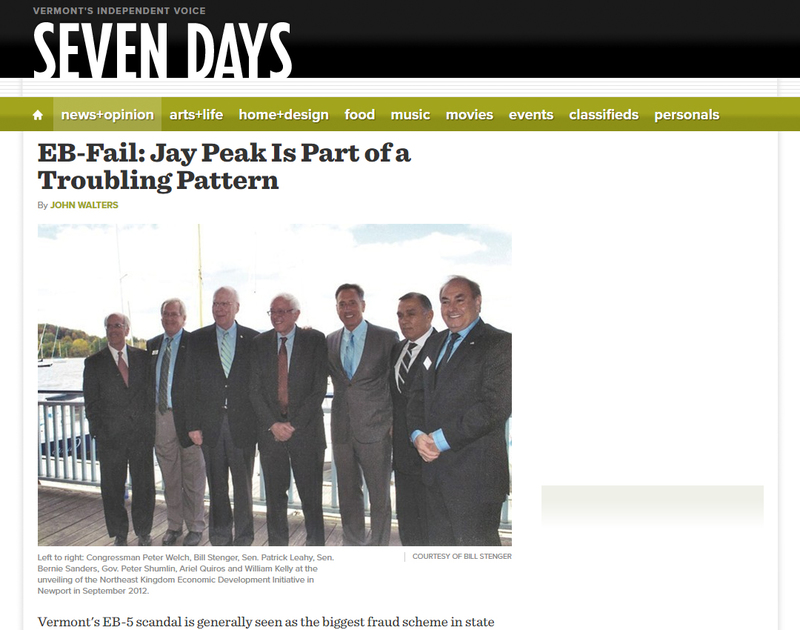

Left to right: Congressman Peter Welch, Bill Stenger, Sen. Patrick Leahy, Sen. Bernie Sanders, Gov. Peter Shumlin, Ariel Quiros and William Kelly at the unveiling of the Northeast Kingdom Economic Development Initiative in Newport in September 2012.

Vermont's EB-5 scandal is generally seen as the biggest fraud scheme in state history and in the 25 years of the federal EB-5 program. Unless there's a stunning courtroom reversal, the fraudulent investment vehicles created under the Jay Peak Resort umbrella will add up to tens of millions in pilfered funds and an estimated $200 million in funds diverted from legal purposes.

And you know what? It's worse than you think.

Well, the fraud itself may not be that much worse. But the failure of the state officials responsible? Newly assembled details are downright appalling, and much information has yet to be made public.

Just ask Anne Galloway, founder and editor of VTDigger.com. Her team has spent years uncovering the scandal. And yet, "We are nowhere near finding out exactly what happened," she says. Many documents have been withheld from public disclosure due to pending court cases, and Galloway's efforts continue to be hamstrung by Vermont's exemption-riddled public records law.

There have been recent developments in the EB-5 case. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services ordered the shutdown of Vermont's EB-5 Regional Center. And the state Department of Financial Regulation released a report on the history of the Vermont center that lays out, in a matter-of-fact way, a truly distressing narrative that merits further attention.

A bit of background. The EB-5 program was created in the early 1990s. Vermont established its own regional center in 1997, which was a rarity in the EB-5 system. Most regional centers were privately operated, while Vermont's was overseen by the Agency of Commerce and Community Development. (Regulatory authority transferred to the DFR in 2014, a move akin to locking the barn door after the horse has been stolen.)

The report finds that the commerce agency's regulation was sorely lacking in three critical areas: resources, enforcement authority and financial expertise.

At first, that wasn't a big deal. "It was a very sleepy program," says DFR Commissioner Michael Pieciak. "We didn't have our first project until 2006. Only when the Great Recession hit and capital was hard to come by did the EB-5 program take off nationally and also in Vermont."

As the program grew, the commerce agency's oversight remained in sleepy mode.

The bulk of EB-5's expansion was generated by the Jay Peak boys, Bill Stenger and Ariel Quiros. Their first application, filed in 2006, sought to raise $17 million. By 2013, Jay Peak had launched five more projects worth a total of $350 million. Its ventures accounted for 80 percent of the Vermont Regional Center's responsibilities.

The mere fact that Jay Peak exploded so dramatically would seem to have warranted special scrutiny. Instead, Galloway says, it got "special treatment from the state. It was never asked to pay administrative fees. The state would have collected a couple million dollars, which would have paid for the cost of oversight."

The commerce agency simply muddled along. "There was usually one individual ... doing all the work," Pieciak says. Agency staff, he adds, lacked the financial expertise and enforcement power to effectively manage a booming EB-5 regional center. And warning signs went unheeded, including complaints from Jay Peak investors in 2011 and a whistleblower in 2012.

Until the whole thing blew up, officials and officeholders, up to and including Vermont's congressional delegation, were more than happy to promote Jay Peak as a miracle cure for the Northeast Kingdom's chronic economic woes.

Vermont was not alone in this imbroglio. As EB-5 mushroomed, scandals followed suit. "The [federal] Securities and Exchange Commission had brought dozens and dozens of enforcement actions, some of them high profile," says Pieciak.

Which is no excuse for what happened in Vermont, mostly during Peter Shumlin's first two terms as governor. That's when Jay Peak went hog wild: Its assurances were accepted at face value, and regulation remained minimal.

The former Shumlin administration officials responsible are assiduously avoiding the matter.

"I would refer everything to the incumbent secretary of commerce or the Attorney General's Office," says former commerce secretary Lawrence Miller. His successor, Patricia Moulton, who is now president of Vermont Technical College, did not respond to requests for comment.

What's worse, the Jay Peak scandal is not unique in recent history. When it comes to economic development, Vermont has a track record of ignoring signs of trouble and accepting assurances from private-sector entities at face value.

For example, take a look at VTDigger's recent series on the contamination of groundwater in the Bennington area with the toxic chemical PFOA, produced by the ChemFab factory that made Teflon. It reveals the same pattern: state officials turning a blind eye to potential trouble until it's far too late. The results are hundreds of tainted wells and health consequences for who knows how many people.

"What happened with ChemFab is not so dissimilar from the lack of oversight with Jay Peak," says Galloway. "The pattern is a little bit disturbing."

A little bit, indeed.

There are also parallels in Vermont's disgraceful treatment of its waterways. The state failed to take effective action until a lawsuit filed by the Conservation Law Foundation and an order from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency forced its hand. The results of the state's failure to effectively regulate nutrient flows is currently, and disgustingly, on display at Lake Carmi, whose waters are covered by a layer of thick toxic algae.

Even as they call for termination of the Vermont Regional Center, federal officials acknowledge that state regulation of EB-5 improved markedly after 2014, when oversight was shifted from the commerce agency to the DFR. But that only happened after the problems at Jay Peak had grown too big to ignore. Or fix.

These actions have consequences that will take years to sort through. The Jay Peak scandal has cost foreign investors millions and imperiled their immigration status, and the legal battles have only just begun. The ChemFab plant closed in 2002, but cleanup efforts will continue for years — and the repercussions for people's health will play out for decades. As for our waterways, the effort to simply prevent further harm will cost hundreds of millions of dollars. We're not even talking about an actual cleanup. And the state has yet to figure out how to pay those bills.

In the short term, it's easy to accept the blandishments of economic saviors and ignore the whiffs of smoke that gradually grow larger and darker. And it's understandable, in a way. State officials are rightly preoccupied with boosting the economy and creating jobs.

But the consequences of a scandal can far outweigh the short-term benefits of ignoring signs of trouble. The Bennington plant provided 90 good-paying factory jobs for more than 40 years, but how do you balance that against tainted wells, lost property value, and, especially, a lifetime of health consequences and fears for former workers and nearby residents?

It would be comforting to believe that the state has learned valuable lessons from its failures. But recent history doesn't inspire confidence.

Media Note

Let's talk about a money-losing enterprise in a declining industry. Now let's say its owner is looking to sell. Doesn't sound promising, does it?

That's the situation with Vermont Life, the 71-year-old publication owned and operated by the State of Vermont. But the picture isn't nearly as dire as it would seem.

Indeed, one industry expert sees Vermont Life as a hot property with loads of untapped potential. And state Tourism and Marketing Commissioner Wendy Knight, whose department is home to the magazine, says, "Oh yeah, absolutely!" when asked if she expects plenty of offers.

To be clear, Vermont Life isn't necessarily for sale. But the state has issued a request for proposals with a deadline of November 17.

"We were required by the legislature to issue an RFP exploring options for Vermont Life," says Knight. "One of the options is selling the magazine. It could also be a licensing arrangement or partnership."

Vermont Life has been losing money, accumulating a deficit of $3 million. In these tight budget times, Gov. Phil Scott and state lawmakers across party lines have grown weary of picking up the tab. Hence the legislative mandate for an RFP.

But Samir Husni is quite bullish on Vermont Life. Husni is a journalism professor from the University of Mississippi and a top authority on magazine publishing, known in the industry as "Mr. Magazine."

General travel publications are in decline, but "the majority of state or regional travel magazines are doing well," he says. "I'm sure a publisher would jump in to buy the magazine."

Here's why. Most publishers are heavily dependent on declining ad sales and earn surprisingly little from actually selling magazines. Vermont Life's biggest revenue source is subscriptions, while it gets less than one-third of its revenue from ad sales. Plus, it has a strong third income stream — product sales for items like calendars and note cards, which are almost as lucrative as advertising.

Husni believes that Vermont Life's struggles are largely due to state control. "When you're connected to a state government, you don't have the freedom to run the magazine the way you might want to," he says. That's even more important in the digital age, when publishers need to be nimble.

He speculates that the most likely bidders will be Vermont-based publishers and entrepreneurs, which would be good news for the state. Its RFP expresses a preference for keeping operations within Vermont and retaining current staff.

So, who might those bidders be?

"Vermont Life is a viable property, without question," says Adam Howard, editorial director and CEO of Backcountry Magazine and an executive with its Jeffersonville-based parent company, Height of Land Publications. "We're reviewing the RFP now."

Other Vermont-based media figures are not ready to commit — including (full disclosure) my boss, Seven Days publisher and coeditor Paula Routly, who's been out of state since the RFP was issued.

"Once I get back to Vermont, I'll look over the RFP with my team," she wrote in an email. "At that point, we'll decide if we're going to bid on it."

Philip Jordan, editor and publisher of Vermont Magazine, offered a quick "no comment."

"We have no interest," says Robin Turnau, president and CEO of Vermont Public Radio. "We are working hard to focus on what we do and do it really well."

The last word goes to Mr. Magazine, who has some advice for Routly. "This crazy magazine consultant from Mississippi says 'Seven Days should buy it.'"

Mentions

- Vermont EB5 Regional Center

- Ariel Quiros

- Bill Stenger

- Peter Shumlin

- Patrick Leahy

- Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development RC

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Litigation Cases

- State of Vermont vs Bill Stenger & Ariel Quiros

- UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION vs Ariel Quiros & Bill Stenger

States

- Vermont

Securities Disclaimer

This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to sell shares or securities. Any such offer or solicitation will be made only by means of an investment's confidential Offering Memorandum and in accordance with the terms of all applicable securities and other laws. This website does not constitute or form part of, and should not be construed as, any offer for sale or subscription of, or any invitation to offer to buy or subscribe for, any securities, nor should it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied on in any connection with, any contract or commitment whatsoever. EB5Projects.com LLC and its affiliates expressly disclaim any and all responsibility for any direct or consequential loss or damage of any kind whatsoever arising directly or indirectly from: (i) reliance on any information contained in the website, (ii) any error, omission or inaccuracy in any such information or (iii) any action resulting therefrom.