How a U.S. Visa-for-Cash Plan Funds Luxury Apartment Buildings

New York’s Hudson Yards project, to be largely above a rail site, is partly financed by a program giving foreigners residence for U.S. investment. PHOTO: TIMOTHY FADEK FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The cluster of luxury apartment buildings and office towers rising in a development west of midtown called Hudson Yards seems a world apart from the low-income housing projects of upper Manhattan.

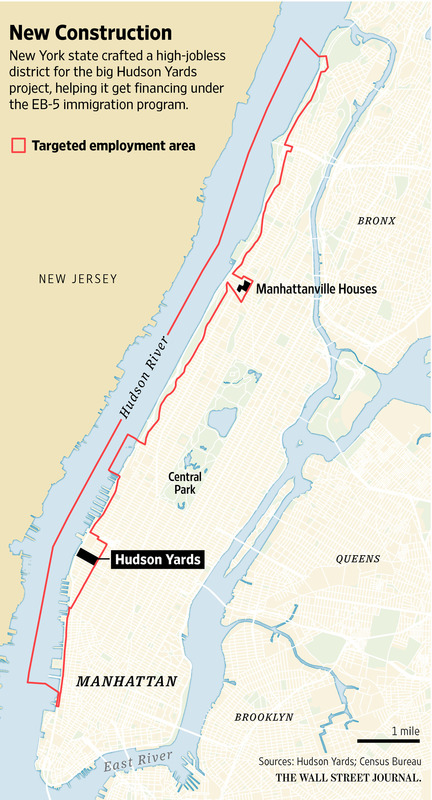

But for purposes of an immigration program that helps finance Hudson Yards, it and Harlem’s Manhattanville public-housing towers are in the same district: a stringy one connected by three Census tracts that run along the Hudson River.

Merging, on paper, the affluent midtown neighborhood and the struggling one uptown placed Hudson Yards in a community with an overall high unemployment rate, positioning developer Related Cos. to gain low-cost financing from foreigners seeking green cards.

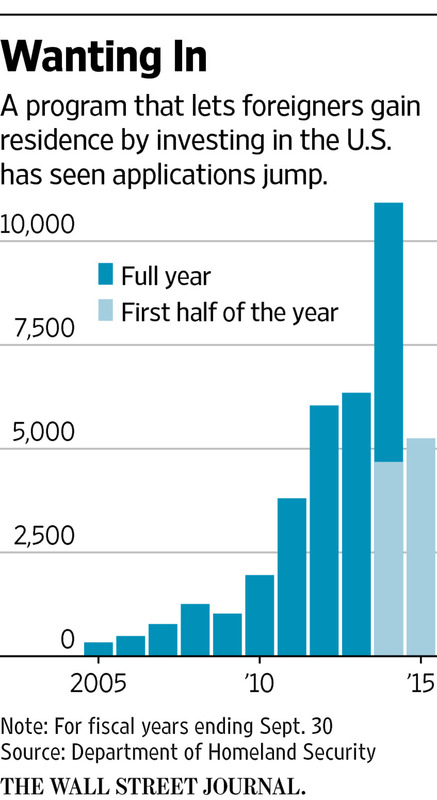

The program through which that happens, known as EB-5, enables foreign nationals to obtain U.S. permanent-resident status by putting up money for new business ventures that create American jobs. It gives ventures in high-unemployment and rural areas a special status to encourage investment. But as the program’s popularity has soared in recent years, the bulk of immigrant investment is going to projects that are located, like $20 billion Hudson Yards, in prosperous urban neighborhoods.

On Sept. 30, a key piece of the EB-5 program is expiring. As Congress prepares to take up reauthorization, some lawmakers are questioning the way the program is being used, and a fight is brewing.

“The incentives Congress created to direct EB-5 investment to rural areas and urban areas plagued by high unemployment have been abused,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.), co-sponsor of a reauthorization bill that would prevent projects in affluent urban neighborhoods from getting high-jobless-area benefits.

Echoing this sentiment, U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson has proposed steps “to prevent gerrymandering” designed to portray projects as being inside high-unemployment districts, Mr. Johnson wrote in an April letter to Mr. Leahy and Senate co-sponsor Charles Grassley (R., Iowa).

A primary concern is that the use of EB-5 financing for high-price condo and office towers sops up the program’s capacity and leaves poorer communities out in the cold. No more than 10,000 visas that lead to permanent-resident status can be given out each year under the program. It hit the limit in the fiscal year ended Sept. 30, 2014.

Though statistics aren’t made public on individual projects, a recent paper by two New York University professors tracked 25 large business startups that have turned to the EB-5 program to raise a total of more than $4.5 billion in financing. Twenty-two were urban real-estate projects, including 14 in prime Manhattan neighborhoods and others in Seattle and on the Las Vegas Strip.

Related, the Hudson Yards developer, said that it follows all federal and state rules and that the project’s impact isn’t limited to Manhattan’s west side.

The EB-5 money “allowed us to immediately create thousands of jobs all over the city offering tangible regional economic benefits and direct benefits to areas of high unemployment,” said a spokeswoman for Related. Hudson Yards “unequivocally would not be as far along as it is today without this capital,” she said.

Related is the single largest user of EB-5 financing. By its own measure, it accounts for about 20% of the dollars being raised through the program today. The closely held company used the program to raise $600 million for a first phase of Hudson Yards last year and is in the process of raising another $600 million for a new office tower and a retail hub.

Crafting a neighborhood

Key to doing so is having the surrounding community designated a Targeted Employment Area, meaning one where the jobless rate is at least 150% of the national average. That status lets foreign investors move toward a U.S. green card by putting up $500,000, typically as a loan. If the project isn’t in a Targeted Employment or rural area, the foreign investors have to pony up $1 million, a level that greatly reduces participation.

The neighborhood immediately around Hudson Yards includes Manhattan’s tony West Chelsea. Unemployment in the local Census tract was just 4.9% in 2012—below the national rate—according to a letter sent in May 2013 from a New York state labor official to Empire State Development Corp., a state economic-development agency.

“The current minimum threshold to qualify as a Targeted Employment Area is 12.2%,” said the 2013 letter, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. “For your consideration, we developed an alternative area.”

State labor officials added four additional Census tracts—three along the banks of the Hudson plus one that reaches into West Harlem. The unemployment rate of the combined five tracts, said the letter: 18.1%.

As this shows, it is state government that typically fashions districts to meet the EB-5 program’s unemployment-rate test. Federal regulations permit this; they defer to states to draw the maps that define a project’s geographic area, so long as Census tracts they lump into a single community are contiguous.

State governments—eager for economic development and with little stake in federal immigration policy—tend to side with developers who want their projects to qualify as easily as possible for financing.

Empire State Development, the state body that designated Hudson Yards as being in a high-unemployment area, defends the practice for this project and others, saying they spawn jobs and benefits for people all around a city and region. The EB-5 program “has been used to create tens of thousands of jobs for New Yorkers across the state,” said a spokeswoman for the agency.

In Congress, developers’ supporters reject criticism of how the immigration program is used to finance construction and applaud it as an economic development tool. “Jobs at no government cost is jobs at no government cost,” said Rep. Mark Amodei, a Nevada Republican who is sponsoring reauthorization legislation that would mostly keep EB-5 as it is. He said he was open to changes to boost rural and poor areas but concerned about making the program too complex.

An advocacy group backed by developers called the EB-5 Investment Coalition is pushing to avoid changes that would curtail the program’s use. Related, a member of the coalition, spent $330,000 on lobbying related to immigration policy during the second quarter, federal lobbying disclosures show.

The coming debate in Congress stands to bring the program its greatest scrutiny since it was created in 1990.

The idea was simple: An aspiring immigrant would help finance a new or expanded business in the U.S., especially in capital-starved areas. If the investment was determined to have created at least 10 jobs per investor, measured after two years, members of the foreign investor’s family would be granted U.S. permanent-resident status. The investment could be at the lowest level—$500,000—if projects were in “areas that can use the job creation the most,” a sponsor of the provision, the late Sen. Paul Simon (D., Ill.), said at the time.

For years, the program wasn’t widely used. It accounted for only a few hundred immigrant visas annually, with money flowing to projects such as a ski slope in Vermont and small projects on closed military bases.

A change in 2009

Things began to change in 2009, amid two shifts. The agency overseeing the program—the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services unit of the Department of Homeland Security—let the job-creation tally count more construction jobs if they last at least two years. And banks all but shut off credit for construction projects amid the economic slump.

Real-estate developers discovered EB-5. Money from foreign investors, primarily Chinese, began to pour into major developments around the U.S., typically supplementing more-senior debt. A hotel and apartment project in Washington raised more than $40 million through the program. A W hotel in Hollywood raised $20 million. A planned 16-tower apartment project connected to Brooklyn’s Barclays Center basketball arena took in $229 million.

Today, the program is at peak popularity. In the fiscal year ended last September, 10,923 foreign investors applied, compared with 6,346 in the prior fiscal year and just 486 in 2006. The majority eventually get approved. China’s recent financial turmoil may decrease future applications given that many have taken hits to their net worth, EB-5 professionals believe. Still, few expect any decrease to be dramatic.

Lenders have since returned to real estate, but developers are attracted by another aspect of EB-5 financing: low cost. Because the foreign investors are after a green card, they have been willing to accept very low interest rates on money they lend, typically for four or five years. Developers save even though they face other costs to use the program.

At 701 Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, a retail and hotel tower going up in Times Square, developers raised about $200 million through EB-5 at an annual interest cost that came to 6% after the middleman fees, said Michael Ashner, chief executive of Winthrop Realty Trust, a partner in the project. That compares with 11% or 12% they would have faced for junior loans through other financing, he said.

“It’s lower-cost capital with favorable terms. That’s why people do it,” Mr. Ashner said.

Many of such projects could easily have been financed on the private market, according to Gary Friedland, who wrote the NYU paper with fellow professor Jeanne Calderon. “It’s a profit enhancement,” he said. “The original argument was more of a ‘but for’ argument,” in which EB-5 was meant to spur projects that wouldn’t otherwise have happened. “That focus has been lost.”

At least 80% of EB-5 money is going to projects that wouldn’t qualify as being in Targeted Employment Areas without “some form of gerrymandering,” estimates Michael Gibson, managing director of USAdvisors.org, which evaluates projects for foreign investors.

Increasingly, the money appears to be flowing to the flashiest projects, which the investors often see as safest, EB-5 professionals say. Among those getting EB-5 money are an office building set to host Facebook Inc. near Amazon.com Inc.’s Seattle headquarters, a boutique hotel in high-end Miami Beach, and a slim Four Seasons condo-hotel in lower Manhattan that sports a penthouse with an asking price above $60 million. In all of them, geographic districts were crafted to include higher-unemployment areas.

Some left out

Meanwhile, some wanting to raise money for projects in rural areas and low-income parts of cities say they find it increasingly hard to compete. Evan Daniels has been trying for four years to raise about $40 million through the EB-5 program for a door-manufacturing plant in the rural southwestern Missouri town of Lamar.

“The harder we worked on this, the more we found the money was going to L.A. and New York,” he said.

Joseph Walsh, a consultant who discussed the issue with Mr. Daniels, said finding foreign investors for rural manufacturing projects in the U.S. was a hard lift, particularly with competition from urban areas. Mr. Walsh said he was frustrated by developments he views as misusing the EB-5 law. “We should be using this money in projects that couldn’t be financed” otherwise, he said.

Related, the Hudson Yards developer, was founded by Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross as an affordable-housing-focused builder but is known for large-scale commercial projects in cities that include San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago. Hudson Yards, believed to be the largest private development under way in the U.S., includes a tower around the height of the Empire State Building.

Related decided to plunge into EB-5 financing in 2013 after seeing other developers do so.

In the usual working of the program, brokers recruit foreign investors, and then regional centers bundle their investments. Related, however, set up its own infrastructure to bundle investments. It also formed an exclusive relationship with a Chinese brokerage firm.

The company and its brokers have held a steady stream of events in China for potential EB-5 investors, ranging from a gala featuring a Chinese television personality and flamboyantly dressed dancers to more mundane PowerPoint presentations. Related Chief Executive Jeff Blau said in April that about 300 people were finding investors for the company in China, Vietnam and Korea.

In China, one pitch is speed in obtaining green-card approvals from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Related’s main broker has advertised that EB-5 investors receive initial approvals 11 months faster than the standard wait. That would mark a big advantage, because the average wait is about 14 months. It is unclear how its applications would be processed so quickly. USCIS declined to comment on Related’s applications.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/how-immigrants-cash-funds-luxury-towers-in-the-u-s-1441848965

Mentions

- Michael Gibson

- USAdvisors

- Hudson Yards Manhattan Tower A-1 - A-8

- Related Companies

- Patrick Leahy

- Chuck Grassley

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- Times Square Hotel

States

- New York

Securities Disclaimer

This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to sell shares or securities. Any such offer or solicitation will be made only by means of an investment's confidential Offering Memorandum and in accordance with the terms of all applicable securities and other laws. This website does not constitute or form part of, and should not be construed as, any offer for sale or subscription of, or any invitation to offer to buy or subscribe for, any securities, nor should it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied on in any connection with, any contract or commitment whatsoever. EB5Projects.com LLC and its affiliates expressly disclaim any and all responsibility for any direct or consequential loss or damage of any kind whatsoever arising directly or indirectly from: (i) reliance on any information contained in the website, (ii) any error, omission or inaccuracy in any such information or (iii) any action resulting therefrom.