Developer's path to Philadelphia waterfront littered with failed projects

Developer Jeffery Kozero wants to remake a swath of South Philadelphia’s Delaware River waterfront into Philadelphia’s version of Miami Beach. Imagine 10 towers — up to 34 stories — overlooking the Delaware in what would be the city’s biggest residential project in memory.

But if past performance counts, the developer might not be up to that ambitious vision.

From the Chesapeake Bay shores to the streets of east Baltimore to central Pennsylvania’s farmland, Kozero has left a trail of unfinished houses, unhappy customers, and unpaid contractors, at one point drawing sanctions from Maryland regulators.

That history looms large as he now wants to play an out-sized role in determining how Philadelphia’s waterfront is developed, seeking wide-ranging changes to carefully thought-through rules governing building heights.

Baltimore architect David Gleason, who once sued Kozero over unpaid invoices, offered his own assessment.

“I would be very cautious about Jeff Kozero,” Gleason said. “He left a lot of people high and dry.”

Kozero declined to be interviewed for this article, explaining that he was recovering from a medical procedure. He defended himself, however, in a written response to questions late last month.

“If you inspect the record of any developer, you are sure to find a history of litigation,” he said. “Given the size, scope and number of projects I’ve been involved in, disagreements, disputes and lawsuits are inevitable.”

Kozero was invited to share examples of successful projects he’s worked on, but offered none.

The Philadelphia plan proposed by his current company, K4 Associates LLC, calls for a 10-tower, 2,000-unit project on 26 waterfront acres between Reed Street and Washington Avenue purchased from the city’s sheet-metal workers union local.

It includes towers that blast past limits of 244 feet — or about 25 stories — imposed by the Central Delaware Overlay zoning district four years ago for an area from Port Richmond to South Philadelphia.

The rules are designed to keep waterfront building heights in line with surrounding neighborhoods. They were forged over months of negotiations that included neighborhood groups, property owners, and open-space advocates.

They also aim to stop zoning changes for projects that overshoot demand and fail, yet increase the market value of the underlying land to a point that it is economically difficult to develop going forward.

The result of that is blight, said Matt Ruben, chairman of the Central Delaware Advocacy Group, a coalition of river-adjacent neighborhood associations.

“We’re concerned about projects that can get zoning, but can’t actually be built,” Ruben said. “It’s important not to enable speculative behavior.”

City Councilman Mark Squilla, whose district includes Kozero’s site, introduced legislation in the spring to change the overlay rules to accommodate K4’s plans but had Council delay consideration of the bill before holding a final vote.

He has said he’s working on a revised plan that incorporates input from critics of the earlier legislation.

State Rep. William Keller (D., Phila.), meanwhile, has vouched for Kozero’s request for $44 million from the state Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program.

“I think this is a good development for the city, for the region, and especially for the district,” said Keller, adding that he trusts that K4 had adequately studied the market. “I give it my full support.”

But a close look at Kozero’s history — gleaned through interviews, public records, and media coverage — suggests that Keller’s confidence may be misplaced.

Kozero graduated from Penn State in 1978 with a degree in water resources engineering technology, a university spokeswoman said. He did not earn the architecture degree claimed on his LinkedIn profile, according to the spokeswoman.

He blamed the inaccuracy on a social media consultant in charge of his web presence and said it is being corrected.

In the mid-2000s, Kozero was running Empire Homes LLC, which built homes in southern Maryland.

Among his customers were Alan and Donna Spealman, who ordered a home in 2005 on land near the Chesapeake Bay in Lexington Park, Md.

In records with the Maryland Attorney General’s office’s consumer protection agency, the Spealmans said Empire owed them more than $50,000 after abandoning the building site, leaving behind a faulty septic system and an unfinished driveway.

Contacted by state consumer protection officials on the Spealmans’ behalf, the company refused to pay or submit to arbitration, according to division records.

Kozero disputed that account, saying he had gone to arbitration and that the state found the Spealmans’ claim to be “either inflated or incorrect,” although he agreed to pay the couple $9,500 to complete their driveway and update their home warranty.

He said he has records reflecting his version of events, but did not immediately respond to a request for them.

Another customer, Theresa Newton, said in an interview that she paid Kozero’s firm nearly $400,000 in 2005 for a custom-built house in Great Mills, Md., that her wheelchair-bound mother could easily navigate.

The house that was delivered had raised molding between rooms — “speed bumps,” Newton called them — that her mother couldn’t traverse, and a basement outfitted with too few sump pumps to keep the space from flooding, Newton said.

“I definitely wouldn’t recommend them to anybody,” said Newton. “They really didn’t put the house together the way they were supposed to.”

Kozero said he does not recall Newton or her house.

“As the CEO and owner of Empire, which was developing and building multiple subdivisions in several states, I did not have direct contact with most home buyers,” he said.

About that time, Kozero was also pursuing opportunities in Baltimore renovating blighted rowhouses.

Gleason, the architect, said Kozero contracted him around 2006 to help design the project.

But he wasn’t paid for his work, documented in a legal claim for $11,160 decided in his favor in 2009, Baltimore court records show.

Kozero said Gleason was not paid because of “inferior” work that did not qualify for construction permits.

Emails submitted as part of Gleason’s lawsuit tell a different story. In one, Kozero apologizes for not paying the architect, blaming the economy.

Kozero’s lender on the Baltimore project, Sandy Spring Bank, also went unpaid by Kozero after he defaulted on a $1.5 million loan, according to court records. Kozero said he worked with the bank to locate another borrower to assume his debt.

Kozero was then pursuing an even bigger venture in rural Adams County, Pa. where he gained approvals for two developments totaling 740 units over 54 acres. The proposal was abandoned when the housing market unraveled in 2007.

Kozero said his project was one among many derailed by the real estate downturn.

“As I recall, the whole world economy contracted at that time,” he said.

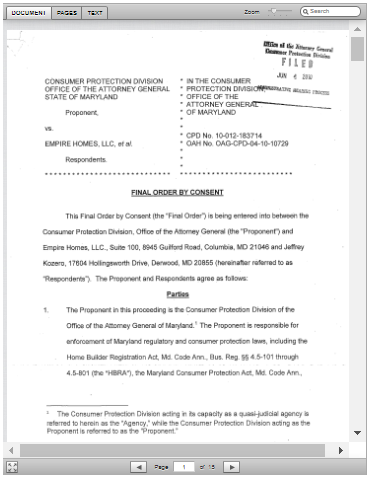

Kozero later came into the sights of the Maryland attorney general’s office for failing to report at least 30 lawsuits against him by lenders, contractors and others.

In June 2010, the developer signed a consent decree in which he agreed to pay $20,000 in retribution.

Kozero said he had worked to pay lenders, contractors and others as much as he could during the downturn, when banks abruptly withdrew or held back funding for real estate projects.

He agreed to the settlement, he said, to save “time, expenses and headaches” for all involved.

By then, Kozero was running a new company formed to build a broadband internet network in and around Northumberland County using federal stimulus funds. His application for about $100 million in grants and loans was declined, and the project was never built.

Kozero soon seized on to a new way to finance his ventures: the EB-5 immigrant visa program, which allows foreign nationals to earn U.S. residency by investing in big, job-creating businesses and projects here.

By July 2012, Kozero had founded the Three Streams Regional Center, which gained federal authorization to sponsor projects for investment by overseas visa-seekers.

Within a few years, Philadelphia developer Eric Blumenfeld had hired Kozero to help build apartments and shops on part of the Sheet Metal Workers International Association Local 19’s waterfront property in partnership with the union.

Kozero’s access to funds through his EB-5 regional center was one reason he got the job, Blumenfeld said.

In 2015, Kozero took over as developer, with his local firm, K4 Philadelphia LLC, acquiring an 18-acre river-facing section of the property from Blumenfeld and the union for $10 million.

Kozero and his partner on the project, former Sheet Metal Workers local head Thomas J. Kelly, have said they are negotiating to buy the remaining eight-acre section from the union to round out the development site.

Among the lenders behind $17.8 million in mortgages on the acquired land is an entity Kozero controls through Three Streams, records show. Despite that, Kozero said Three Streams is not involved with the proposal.

At this point, Kozero said because he had enough “interest from equity investors and banks, K4 Philadelphia does not need the EB-5 investment,” he said.

He did not respond to a request to identify those backers, but touted the involvement of Wells Fargo & Co. as the prospective underwriter of a government-backed loan sought for the development as “Confidence in K4 Philadelphia, LLC, and in the ultimate success of this project.”

Asked about his assertion, a Wells Fargo spokesman said his company is no longer involved in the project.

Mentions

States

- Pennsylvania

Videos

Subscribe for News

Site Digest

Join Professionals on EB5Projects.com →

Securities Disclaimer

This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to sell shares or securities. Any such offer or solicitation will be made only by means of an investment's confidential Offering Memorandum and in accordance with the terms of all applicable securities and other laws. This website does not constitute or form part of, and should not be construed as, any offer for sale or subscription of, or any invitation to offer to buy or subscribe for, any securities, nor should it or any part of it form the basis of, or be relied on in any connection with, any contract or commitment whatsoever. EB5Projects.com LLC and its affiliates expressly disclaim any and all responsibility for any direct or consequential loss or damage of any kind whatsoever arising directly or indirectly from: (i) reliance on any information contained in the website, (ii) any error, omission or inaccuracy in any such information or (iii) any action resulting therefrom.